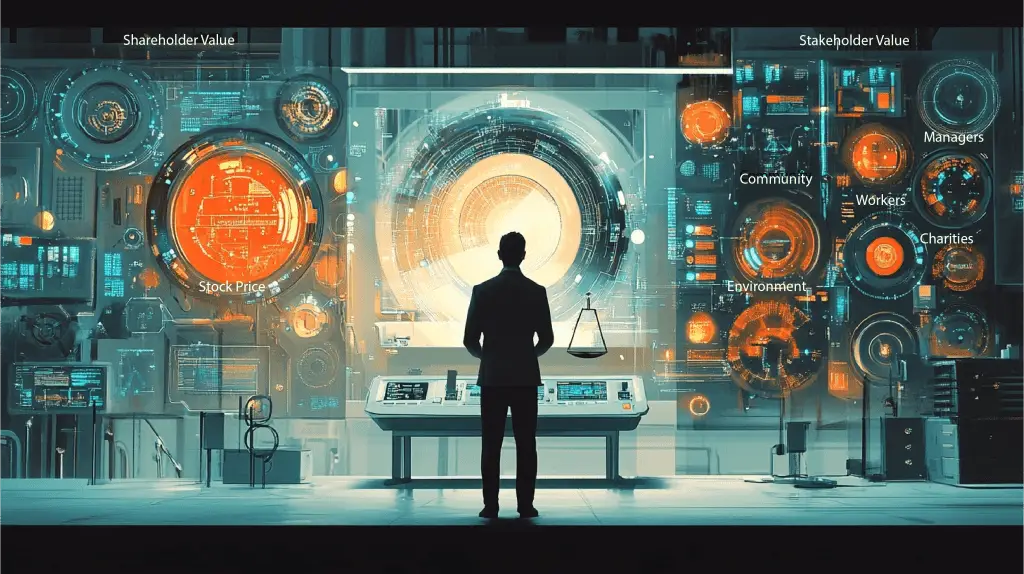

Last week, I shared my thoughts on the rise of stakeholder capitalism and its potential to transform modern business. Today, I’m taking a step back to examine some crucial counterarguments that deserve our attention. After all, even the most promising ideas need thorough scrutiny.

The Accountability Dilemma

- Too Many Masters, No True North When everyone’s a stakeholder, who’s really in charge? It’s like trying to steer a ship while taking directions from the entire crew, passengers, and even the fish in the sea. In my experience, this diffusion of responsibility can lead to decision paralysis or, worse, provide convenient cover for poor management decisions. “We’re doing it for the stakeholders” can become the corporate equivalent of “The dog ate my homework.”

- The Measurement Maze Try measuring “social good” with the same precision as quarterly earnings – it’s like trying to weigh clouds. Without clear metrics, how do we know if a company delivers on its stakeholder promises? The lack of standardized measurement tools makes it dangerously easy for companies to claim success while actually achieving very little.

The Economic Reality Check

- Market Efficiency Blues Free markets work best with clear objectives. By muddying the waters with multiple, often conflicting goals, stakeholder capitalism might actually reduce overall economic efficiency. It’s like asking a chef to simultaneously cook a vegan dish, a steak, and a kosher meal in the same pan – something’s got to give.

- Resource Allocation Headaches When companies divert resources to address various stakeholder interests, are they still playing to their strengths? I’ve seen businesses tie themselves in knots, trying to be all things to all people, ultimately becoming less effective at their core mission.

The Democracy Question

- Unelected Social Engineers Here’s a thought that keeps me up at night: Should corporate executives who no one elected be making major social policy decisions? When embracing stakeholder capitalism, we ask business leaders to act as quasi-governmental agents. That’s a lot of power to hand over to the corporate suite.

- The Power Paradox By expanding corporate influence into social issues, we might actually be creating more significant problems than we’re solving. It’s like giving Superman additional superpowers – it sounds great until you realize he might only sometimes use them the way you’d hoped.

Practical Pitfalls

- Competitive Disadvantages In a global marketplace, companies fully embracing stakeholder capitalism might be disadvantaged against more focused competitors. It’s like entering a boxing match with one hand dedicated to solving world peace – admirable but potentially painful.

- Innovation Roadblocks: Could the need to consider multiple stakeholder interests actually slow down innovation? When every decision needs to be filtered through various stakeholder lenses, the pace of progress might shift from a sprint to a crawl.

The Friedman Defense Still Stands

- Shareholder Logic Milton Friedman argued that a business’s social responsibility is to increase its profits. While that might sound cold-hearted, there’s elegant clarity in this approach. When companies focus on profitable operations, they naturally create jobs, drive innovation, and generate tax revenue that governments can use to address social issues.

- Government’s Role Isn’t it more democratic to let elected governments handle social policy while businesses focus on what they do best? Tax systems and regulations provide a more transparent and accountable way to address social needs than corporate initiatives.

Alternative Approaches Worth Considering

- Reformed Shareholder Capitalism: Instead of throwing out the traditional model entirely, why not focus on improving it? Better regulation, enhanced transparency, and strengthened corporate governance might achieve similar goals without the complications of stakeholder capitalism.

- Market-Driven Solutions: Let consumers and investors drive corporate behavior through their choices. If people genuinely value social responsibility, they’ll support companies that demonstrate it – no complex stakeholder model is required.

The Path Forward

Having explored the promise [link to the previous post] and potential pitfalls of stakeholder capitalism, I’m convinced that the truth lies somewhere in between. While the traditional shareholder model has its flaws, stakeholder capitalism might need to be more active in its attempt to solve them.

Perhaps we need a more nuanced approach that preserves the clarity and efficiency of shareholder capitalism while acknowledging broader corporate responsibilities. But that’s just my take—I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Are you more convinced by my optimistic view last week, or do today’s counterarguments raise essential concerns? Let’s continue this crucial conversation in the comments below.